bone age

As I went through paediatric training it took a while for me to develop a special interest, but as I look back, endocrinology, it turned out, had always been the subject for me. I have a degree of distractibility and restlessness that has often stopped me from committing to one thing, and so have tended to stick around in general medicine - here problems are largely untriaged, and the good generalist is adaptable, a jack of all trades and able to manage the common issues efficiently, without losing sight of the rare things that masqerade as something less. The vulnerabilty of any generalist is never the common presentation of a rare problem, it is the rarer presentation of a common problem. And to be honest, by then I had been in training already 5 years, and my head was not completely in my career by that point. I had married, had a baby and was focussing more on my new family.

It was a chance clinic I sat in on my day off, in the hope of getting some training, with Dr Charles Buchanan, paediatric endocrinologist, in an outreach clinic somewhere in Kent, that my life changed. I was post nights, so pretty tired, but Dr B did not come out that way often, and his reputation was famous - so I stayed up and strolled on down to outpatients to wait deferently for him and beg a seat at the back of the room. He arrived late and absent-mindedly started punching the keyboard with single fingers to login, dismissively agreeing for me to sit in as he did. The patients had already started to build as he started through the list. I think by that point he had forgotten I was even there.

And as the patients started to file in one after the other, he came alive, apparently remembering them all with their personal circumstances, and making assessments and delivering advice with the confidence and charisma of a judge. And between the patients, we chatted a bit, mostly about what we had seen, each story the opportunity for an anecdote and a tutorial on the topic. At the end of the day he handed me a paper from his bag on imprinting in prader willi and beckwith wiedemann syndrome. I was hooked. From then my direction changed.

Endocrinology

This is the study of hormones, in particular the identification and management of problems where they don’t work. In children, a lot of this focusses on growth which is a hugely complicated topic and represents a heady mix of rigorous measuring, tests and interpretation of results, coupled with the really human impact of all that overspilling in the clinic room. Endocrinology sits in that space between when is someone too tall or too short - when is it ‘nature’ and when is ‘illness’?

And even within medicine, endocrinology has a particular reputation. It is seen as intellectually difficult and requiring patience as the real diagnosis may take some years to become clear. It is for people who don’t mind playing the long game. In paediatrics it is usually easy to spot the endocrinologist. They have a good working knowledge of all the rarer tests that others steer clear of. Unit of time is the decimal age, already a slightly unfamiliar idea to other medics.

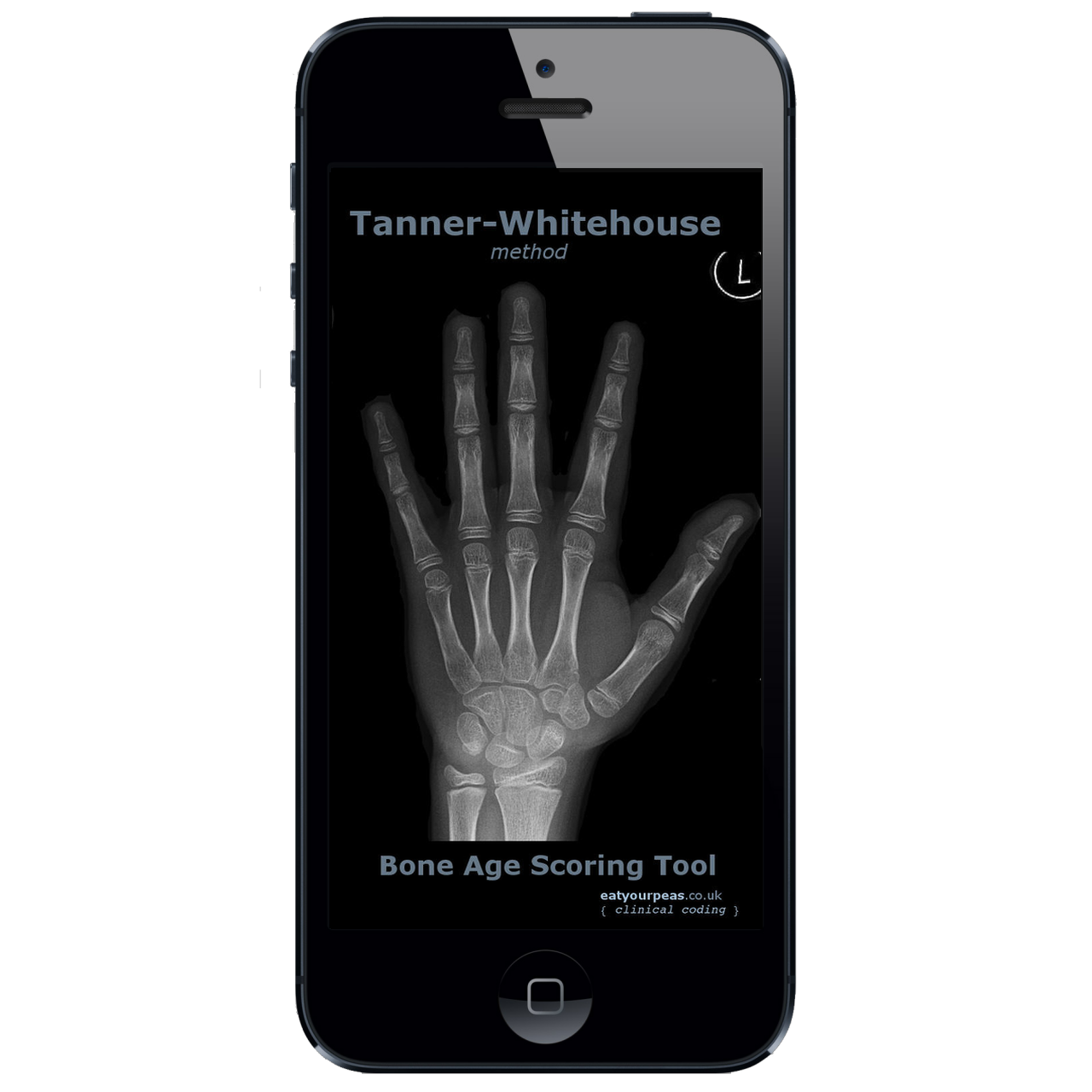

One of the tests occasionally requested in endocrinology is the bone age. It was first thought of as useful in the 1960s, as a way of establishing a ‘skeletal age’ when assessing growth. The bones of children who are late to go through puberty appear younger than those of children who mature at the usual time, as the puberty hormones have not yet been able to influence bone development. This has led to the concept of a bone age, the idea that one can estimate the age of the child from an xray of the left hand alone, and then compare that with their actual age. Whilst there is quite a range of error, the discrepancy between the two numbers could give clues to the underlying reason for the child’s growth problem. Tables have been developed of normal xray changes to expect in healthy children, that form a standard against which to compare results of those presenting to clinics with growth abnormalities.

To medics not familiar with endocrinology, bone age is complicated. It requires a systematic approach to scoring the 20 bones of the hand (13 small bones, and 7 carpals), giving them each a score between A and I, which are then used to generate a raw score against which the bone age can be looked up.

The only way to do this traditionally was with an atlas - now largely out of print, with reference images against which to score the xrays. You never had time to do it in clinic - you had to store up all the names and spend an afternoon at the computer with the atlas balanced on your lap and a cup of tea, typing the scores into the clinical record. The growth charts, where these scores are recorded, were all paper, although the clinical record soon was electronic, so you had to flip between the two. There was no form to type the results into, since the health care record has no concept of a bone age, so it would be written in free text into the notes.

Bone age

This, along with clinic calculator, was my first step into mobile development. Fuelled on by a wish to do this more efficiently, but not knowing how to code, I came across google AppInventor, now a tool for teaching children the concepts of programming. It has a series of blocks on the screen, like jigsaw pieces, which can be linked together to make loops or conditional statements. It was in this way that my first attempt at a bone age calculator came about, painstakingly uploading all the reference data to build it. Sadly I nolonger have images of it, but it was not pretty. For all that, it worked adequately on the smart phones of the early thousands. As time went by, I learnt android, and, once I had got past the confusing curly braces and semicolons, transferred the concepts I had learned to build the first version. Realising that most doctors have iPhones, I knew I would have to make the leap to objective C, and finally splashed out on my first mac. It was a reluctant step, but I have never looked back. My first attempt in XCode made full use of all the user interface tools available:

How do you use it

The original description of bone age involved scoring all 20 bones of the hand, but subsequent reworkings of the system have found accuracy is the same for just the 13 small bones (radius, ulna, proximal first/third/fifth metacarpal, proximal/middle/distal third/fifth phalanges and proximal and distal phalanges of the thumb) as it is for the 7 carpals (scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform, trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate). Bones tend to mature in a proximodistal direction, so the carpals tend to be more mature than the distal phalanges. There are different bone age scores, with Tanner Whitehouse possibly the most preferred by endocrinologists, devised as it was by the UK hero of paediatric endocrinology from the 1960s onwards, James Tanner. I discovered to some surprise a few years ago that James Tanner was actually my mother’s landlord many years ago and her main memory of him was fixing her sink.

The Tanner-Whitehouse system was devised as part of a bigger project looking at growth in the context of nutrition using serial x-rays of children in care in Harpenden, Hertfordshire in the post war years. The ethics of this has been discussed in some detail in the journals. It involves an AP xray of the left hand (irrespective of handedness). The user works through the bones, assessing the epiphyses of each and scoring them between A and I (or A and H depending on the bone) using the detailed criteria as described in the original atlas. The earlier scores are less reliable as mineralisation has not really started - many people don’t do bone ages in the under 5s anyway. Most of the criteria have a concept of whether mineralisation is as wide as or wider than the epiphysis, and also a concept of ‘capping’: this happens usually around puberty. The process is nicely described in the atlas its self or in this review.

The screen is portrait view. The radio buttons down the left hand side set the grade - toggling between them updates the description and the image guide. Pressing the icon over the image flips between x-ray view and cartoon view.

Saving the grade

Selecting the grade will not include it in the final score though. To save the selection for each bone, press the plus button on the bottom right of the screen. This will cause the description panel and image to slide into the middle of the screen and the grade radio buttons to fade out. A diagram of the bones with the bones scored filled in red appears for 2-3 seconds to signal which bones have been scored. Once the minimum number of bones have been scored, a toast notification at the foot of the screen appears and the calculate button is enabled. The reports the result to the screen.